Grotere foto

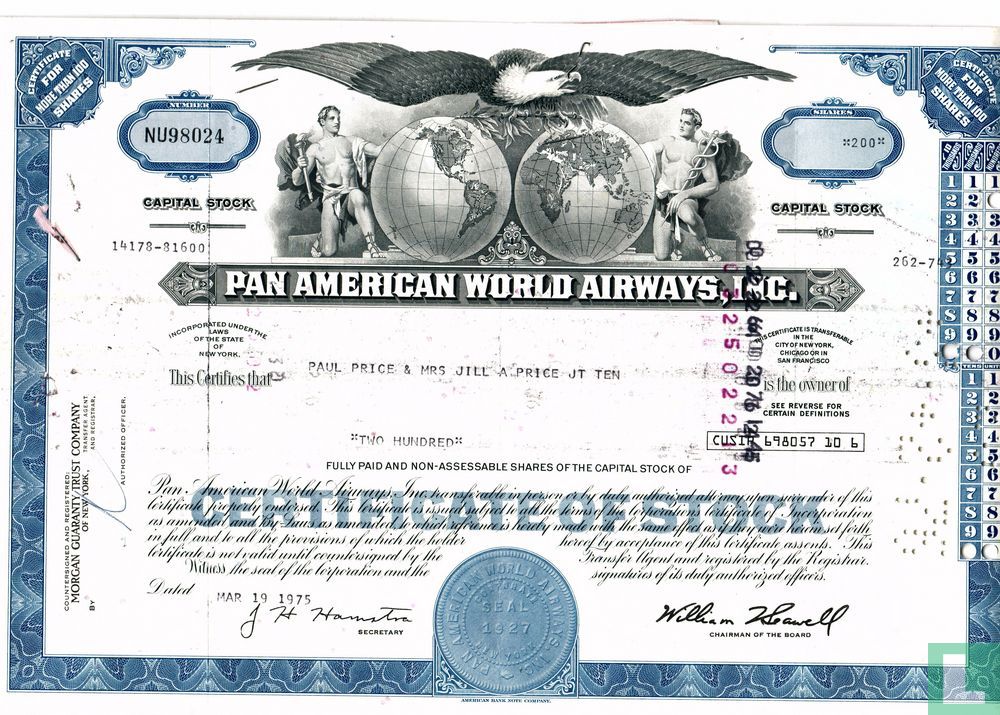

Pan American World Airways, Inc., Certificate for more than 100 shares, Capital stock, w/o par value

Catalogusgegevens

LastDodo nummer

1639385

Rubriek

Waardepapieren

Titel

Pan American World Airways, Inc., Certificate for more than 100 shares, Capital stock, w/o par value

Uitgevende instantie

Soort

Nominale waarde

Rentepercentage (obligatie)

Branche

Land van uitgifte

Plaats van uitgifte

Jaar van uitgifte

Drukker

Oplage

Decoratieve waarde

Zeldzaamheid

Afmetingen

20,5 x 30,5 cm

Bijzonderheden

Handtekeningen facsimile.

Stuk op naam.

Ontwaarding door perforatie en/of stempeling.

CUSIP 698057 10 6

Pan American World Airways, commonly known as Pan Am, was the principal international airline of the United States from the 1930s until its collapse in 1991. Originally founded as a seaplane service out of Key West, Florida, the airline became a major company credited with many innovations that shaped the international airline industry, including the widespread use of jet aircraft, jumbo jets, and computerized reservation systems. Identified by its blue globe logo and the use of the word "Clipper" in aircraft names and call signs, the airline was a cultural icon of the 20th century, and the unofficial flag carrier of the United States.

The Pan Am brand was resurrected twice after 1991, although the reincarnations were related to Pan Am, and each other, in name only. The first operated from 1996 to 1998, with a focus on low-cost, long-distance flights between the U.S. and the Caribbean. It used the IATA airline designator PN. The second was a small regional carrier based in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that operated between 1998 and 2004. It used the IATA code PA, and the ICAO code PAA. Boston-Maine Airways, a sister company of the second reincarnation, still operates the "Pan Am Clipper Connection" brand.

History

Pan American Airways Incorporated was founded on March 14, 1927, by Major Henry H. "Hap" Arnold and partners. Their shell company was able to obtain the U.S. mail delivery contract to Cuba, but lacked the physical assets to do the job. On June 2, 1927, Juan Trippe formed the Aviation Corporation of America with the backing of powerful and politically-connected financiers William A. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, and others; Whitney served as the company's president. Their operation had the all-important landing rights for Havana, having acquired a small airline established in 1926 by John K. Montgomery and Richard B. Bevier as a seaplane service from Key West, Florida to Havana. The Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean Airways company was established on October 11, 1927, by New York City investment banker Richard Hoyt, who served as president. The three companies merged into a holding company called the Aviation Corporation of the Americas on June 23, 1928. Richard Hoyt was named as chairman of the new company, but Trippe and his partners held forty percent of the equity and Whitney was made president. Trippe became the operational head of the new Pan American Airways Incorporated, created as the primary operating subsidiary of Aviation Corporation of the Americas.

The U.S. government had approved the original Pan Am's mail delivery contract with little objection, out of fears that the German-owned Colombian carrier SCADTA (nowadays Avianca) would have no competition in bidding for routes between Latin America and the United States. The government further helped Pan Am by insulating it from its American competitors, seeing the airline as the "chosen instrument" for U.S. foreign air routes. The airline expanded, due in part to its virtual monopoly on foreign airmail contracts.

Trippe and his associates planned to extend Pan Am's network through all of Central and South America. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Pan Am purchased a number of ailing or defunct airlines in Central and South America, and negotiated with postal officials to win most of the government's airmail contracts to the region. In September 1929, Trippe toured Latin America with Charles Lindbergh to negotiate landing rights in a number of countries, including SCADTA's home turf of Colombia. By the end of the year, Pan Am offered flights down the west coast of South America to Peru. The following year, Pan Am purchased the New York, Rio, and Buenos Aires Line (NYRBA), giving it a seaplane route along the east coast of South America to Buenos Aires, Argentina, and westbound to Santiago, Chile, and renaming it Panair do Brasil. Pan Am also partnered with Grace Shipping Company in 1929 to form Pan American-Grace Airways, better known as Panagra, to gain a foothold to Andes countries in South America.

Pan Am's holding company, the Aviation Corporation of the Americas, was one of the hottest stocks on the New York Curb Exchange in 1929, and flurries of speculation surrounded each of its new route awards. On a single day in March, its stock rose 50% in value. Trippe and his associates had to fight off a takeover attempt by the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation to keep their control over Pan Am (UATC was the parent company of what are now Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and United Airlines).

The Clipper Era

While Pan Am was developing its South American network, it also negotiated with Bernt Balchen, of the Norwegian Airline DNL, in 1937 for a co-operative Trans-Atlantic flight to Europe. The agreement was for Pan Am to use its Clippers on flights from New York to Reykjavík, Iceland; DNL would then take over with their Sikorsky S-43 aircraft onwards to Bergen, Norway. This idea was dropped when Pan Am pulled out and instead turned to Britain and France to begin seaplane service between the United States and Europe. Britain's state-owned Imperial Airways was eager to cooperate with Pan Am, but France was less willing to help, because its state carrier Aéropostale was a major player in Latin America and a Pan Am competitor on some routes. Eventually, Pan Am reached an agreement with both countries to offer service from Norfolk, Virginia, to Europe via Bermuda and the Azores using Sikorsky S-40 flying boats. This service was not put into operation in its entirety, but from June 16, 1937, a joint service from New York to Bermuda was inaugurated, with Pan Am using the Bermuda Clipper, a Sikorsky S-42, and Imperial Airways using 'C class' flying boat RMA Cavalier. Pan Am also procured an airmail contract from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

On July 5, 1937, the first commercial survey flights across the North Atlantic were conducted. The Pan Am Clipper III, a Sikorsky S-42, landed at Botwood, in the Bay of Exploits, Newfoundland, Canada, from Port Washington, New York, via Shediac, New Brunswick, Canada. The next day Pan Am Clipper III, piloted by Captain Harold Gray left Botwood for Foynes, Ireland. The same day a Short Empire C-Class flying boat, the Caledonia, under the command of Captain Arthur Sydney Wilcockson, left Foynes for Botwood and landed July 6, 1937, reaching Montreal on July 8 and New York on July 9. These test flights marked the first steps toward the beginning of commercial transatlantic flights.

A fleet of six large long range Boeing 314 flying boats was delivered to Pan Am in early 1939. The new type enabled commencement of a regular weekly transatlantic passenger and air mail service between the US and UK on 28 June 1939. The route was from New York via Shediac, Botwood and Foynes to Southampton. The single fare was $375 — equivalent to $5,300 today. From the outbreak of war, the terminal became Foynes until the service ceased for the winter on 5 October. Throughout the war, Pan Am's Boeing 314s frequently flew over the central Atlantic and worldwide in support of military operations.

Pan Am planned to start land plane service over Alaska to Japan and China, and sent Lindbergh on a survey flight in 1930; however, the ongoing political upheaval in the Soviet Union and Japan made the route unviable. Trippe then decided to start a service from San Francisco to Honolulu, and from there to Hong Kong and Auckland following existing steamship routes. After negotiating rights in 1934 to land at Pearl Harbor, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, and Subic Bay (Manila), Pan Am shipped $500,000 worth of aeronautical equipment westward in March 1935 and ran its first survey flight to Honolulu in April with a Sikorsky S-42 flying boat. The airline won the contract for a San Francisco-Canton mail route later that year, running its first commercial flight in a Martin M-130 on November 22 to massive media fanfare. Later, Pan Am used Boeing 314 flying boats for the Pacific route: in China, passengers could connect to domestic flights on the Pan Am-operated China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) network. The Boeing 314s were also used on transatlantic routes starting in 1939.

The "Clippers"—the name harking back to the 19th century clipper ships—were the only American passenger aircraft of the time capable of intercontinental travel. To compete with ocean liners, the airline offered first-class seats on such flights, and the style of flight crews became more formal. Instead of being leather-jacketed, silk-scarved airmail pilots, the crews of the "Clippers" wore naval-style uniforms and adopted a set procession when boarding the aircraft. However, during World War II most of the Clippers were pressed into the military, with Pan Am flight crews operating the aircraft under contract. During this era, Pan Am pioneered a new air route across western and central Africa to Iran, and in early 1942, the airline became the first to operate a route circumnavigating the globe. Another first was in January 1943, when Franklin Roosevelt became the first U.S. president to fly abroad, in the Dixie Clipper. It was also during this period that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry was a Clipper pilot. He was aboard the Clipper Eclipse when it crashed in Syria on June 19, 1947.

Post-War Developments

After the war, Pan American's fleet was quickly replaced by faster aircraft, such as the Boeing 377, Douglas DC-6, and Lockheed Constellation. For almost 40 years, Pan Am Flight 001 ruled all westbound air travel with a flight that originated in San Francisco and stopped around the world. These stops included Honolulu, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Calcutta, Delhi, Beirut, Istanbul, Frankfurt, London, and finally New York. The westbound flight lasted 46 hours after its first take-off. Meanwhile, Pan Am Flight 002 circled the globe eastbound.

Although Pan Am lobbied intensively to enhance its position as the nation's international airline, it lost that distinction—first to American Overseas Airlines, and later to a number of carriers designated to compete with Pan Am in certain markets, such as TWA to Europe, Braniff to South America, and Northwest Orient to East Asia. In 1950, shortly after starting an around-the-world service and developing the concept of "economy class" passenger service, Pan American Airways, Inc. was renamed Pan American World Airways, Inc.

With strong competition on many of its routes, Pan Am began investing in innovations such as jet and wide-body aircraft. Pan Am purchased the DC-8 and the Boeing 707, which Boeing modified to seat six passengers across instead of five under pressure from Pan Am. The airline inaugurated transatlantic jet service from New York to Paris on October 26, 1958, with a Boeing 707 named the Clipper America.

Pan Am was a launch customer of the Boeing 747, initially ordering 25 of them in April 1966. On January 15, 1970, First Lady Pat Nixon officially christened a Pan Am Boeing 747 at Washington Dulles International Airport in the presence of Pan Am chairman Najeeb Halaby. Rather than breaking a bottle of champagne, Mrs. Nixon pulled a lever which sprayed red, white, and blue water on the aircraft. During the next few days Pan Am flew several of their 747 jets to various major airports in the U.S. as part of a public relations effort, allowing the public to tour the airplanes. Pan Am then began operation of the first commercially scheduled 747 service on the evening of January 21, 1970, when Clipper Victor flew from New York to London. An engine failure caused a delayed departure of several hours on this first flight, but passengers still cheered and drank champagne as the jet finally lifted off from the runway at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Pan Am was also one of the first three airlines to sign options for the Concorde, but like other airlines that took out options—with the exception of British Overseas Airways Corporation and Air France—it did not actually purchase the supersonic jet. It was also a potential customer for the abandoned Boeing 2707, the American supersonic project that never saw service.

In the 1950s, Pan Am diversified into other areas. Some of the businesses that Pan Am bought into included a hotel chain, the InterContinental Hotel, and a business jet, the Falcon. The airline was involved in creating a missile-tracking range in the South Atlantic, and in operating a nuclear-engine testing laboratory in Nevada.

With traffic increasing in 1962, Pan Am commissioned IBM to build PANAMAC, a large computer that booked airline and hotel reservations. It also held large amounts of information about cities, countries, airports, aircraft, hotels, and restaurants. The computer came to occupy the fourth floor of the Pan Am Building, which was then under construction in midtown Manhattan and was to be the largest commercial office building in the world for some time.

Pan Am also built Worldport, a terminal building at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York that was the world's largest airline terminal for many years. It was distinguished by its elliptical, four-acre (16,000 m²) roof, suspended far from the outside columns of the terminal below by 32 sets of steel posts and cables. The terminal was designed to allow passengers to board and disembark via stairs without getting wet by parking the nose of the aircraft under the overhang. The introduction of the jetbridge made this feature obsolete. Continuing the airline's tradition of bold architecture, in Miami, Pan Am built a gilded training building in the style of Edward Durell Stone designed by Steward-Skinner Architects.

At its peak, Pan Am was providing scheduled service to every continent except for Antarctica. Many of its routes were between New York, Europe, and South America, and between Miami and the Caribbean. Starting in 1964, the airline was providing helicopter service between New York's major airports and Manhattan. Aside from the DC-8, the Boeing 707 and 747, the Pan Am jet fleet also included Boeing 720s, 727s (which replaced the 720s), 737s, and Boeing 747SPs, which allowed Pan Am to fly nonstop flights from New York to Tokyo. The airline also operated Lockheed L-1011s, DC-10s, and Airbus A300s and A310s.

The airline also participated in several notable humanitarian flights. Pan Am operated 650 flights a week between West Germany and West Berlin, first with the DC-6B and, in 1966, with the Boeing 727. Pan Am also flew R&R (Rest and Recreation) flights during the Vietnam War. These flights carried American service personnel for R&R leaves in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and other Asian cities.

At its height during the early 1970s, Pan Am's advertising made the airline well known for its trademark slogan, "World's Most Experienced Airline." At this time it was well regarded for its state-of-the-art aircraft and the destinations it served in as many as 160 nations. The airline was respected for the experience and professionalism of its crews; cabin staff were multilingual and usually college graduates, frequently with nursing training. During this period Pan Am's onboard service and cuisine, inspired by Maxim's de Paris, were delivered "with a personal flair that has rarely been equaled." Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis preferred to fly First Class on Pan Am between New York and Athens, even though her Greek husband owned Olympic Airlines.

Downturn

The 1973 energy crisis significantly impacted Pan Am's operational costs. In addition to high fuel prices, low demand for air travel and an oversupply in the international air travel market (partly caused by federal route awards to other airlines, such as the Transpacific Route Case) reduced the number of passengers Pan Am carried, as well as its profit margins. Like other major airlines Pan Am had invested in a large fleet of new 747s with the expectation that demand for air travel would continue to rise, which was not always the case.

On September 23, 1974, a group of Pan Am employees published an ad in the New York Times to register their disagreement over federal policies which they felt were harming the financial viability of their employer. The ad cited discrepancies in airport landing fees, such as Pan Am paying $4,200 to land a plane in Sydney, Australia, while the Australian carrier, Qantas, paid only $178 to land a jet in Los Angeles. The ad also contended that the U.S. Postal Service was paying foreign airlines five times as much to carry U.S. mail in comparison to Pan Am. Finally, the ad questioned why the Export-Import Bank of the United States loaned money to Japan, France, and Saudi Arabia at six percent interest while Pan Am paid 12%.

To remain competitive with other airlines, Pan Am began trying to make inroads in the U.S. domestic market. After several failed attempts to win approval for domestic routes, the enactment of airline deregulation finally allowed Pan Am to begin domestic flights between its U.S. hubs in 1979. On the other hand, deregulation hurt Pan Am since the airline did not have a domestic route system beforehand, a result of Juan Trippe's focus on dominating the overseas market. Meanwhile, airlines with domestic routes were now competing with Pan Am on international routes as well.

Under the direction of Chairman William Seawell, Pan Am grew a domestic-route network overnight by absorbing National Airlines in 1980. However, a bidding war with Texas Air's Frank Lorenzo caused Pan Am to pay far more than the actual value of National Airlines. The combined company continued to accumulate debt due to incompatible fleets (Pan Am had L-1011s with Rolls-Royce engines while National used DC-10s with GE engines), incompatible route networks (National's operations concentrated on Florida), and incompatible corporate cultures. Seawell attempted to save the airline by selling off some of its assets, including the Pan Am Building to MetLife in 1981 and the company's entire Pacific route network to United Airlines in 1985. The extra money was invested in new aircraft such as the Airbus A310 and Airbus A320, although the A320s were never delivered. The airline also started a shuttle service between Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C. Nevertheless, financial losses as well as growing criticism of poor service continued to plague Pan Am.

Pan Am's iconic image also made it a target for terrorists. In an attempt to convince the public that the airline was safe to fly with and to address lapses in its own security, Pan Am created a security system called Alert Management Systems in 1986. The new system did little to improve security. This was further exacerbated by financial concerns, in which the airline decided to keep security at a minimum so as to not inconvenience its passengers and lose business during departure. The FAA fined Pan Am for nineteen security failures, out of the 236 that were detected amongst 29 airlines in December 1988.

The 1980 Pan American World Airways takeover of National Airlines is described as the "Coup of the Decade". The acquisition of National Airlines provided Pan Am with a much needed domestic feeder service for its international route structure. Operations Coordinator Richard Stern of National Airlines is appointed Acting Director of Operations of Pan Am's South-eastern region for his role in facilitating the takeover of the lucrative domestic carrier National Airlines headed up by Bud Maytag (Whitegoods Appliance Giant). Subsequent to the takeover, Mr Stern relocated Pan Am's corporate headquarters from New York to Miami occupying National Airline's former General Offices adjacent to Miami International Airport. Mr Stern believed that the acquisition would hold Pan Am in good stead for the next decade inspite of the impact of deregulation on US Trunk Carriers. January 1, 1980. Pan Am pays a record $USD50.00 per share for the National Airlines stock, described by market speculators as an over-inflated price. William Sewell (Pan Am's CEO & President), claims the price paid was justified due to National's ownership of 95% of their Boeing & Lockeed Fleet. There is no liability, only asset, says CEO Sewell.

Finally, the airline began to fall apart following the 1986 hijacking of Pan Am Flight 73 in Pakistan, in which 20 passengers and crew were killed with 120 more injured, and the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 (Clipper Maid of the Seas) above Lockerbie, Scotland, which resulted in 270 fatalities. Many travelers avoided booking on Pan Am as they had begun to associate the airline with danger. Faced with a $300 million lawsuit filed by more than 100 families of the PA103 victims, the airline subpoenaed records of six U.S. government agencies, including the CIA, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the State Department. Though the records suggested that the U.S. government was aware of warnings of a bombing and failed to pass the information to the airline, the families claimed that Pan Am was attempting to shift the blame.

The Gulf War, which began in August 1990, brought transatlantic air traffic to a trickle. On October 23, 1990, the airline sold off its profitable London Heathrow routes, arguably Pan Am's biggest international destination, to United Airlines. (The routes would be transferred in April 1991, after British and American regulatory approvals.) This left Pan Am with its only London flights being two daily flights to Gatwick. Nevertheless, Pan Am was forced to declare bankruptcy on January 8, 1991. Delta Air Lines purchased the remaining profitable assets of Pan Am, including its remaining European routes and the Pan Am Worldport at JFK Airport, and injected some cash into a smaller Pan Am predominantly serving the Caribbean and Latin America. During that time, Pan Am continued to incur heavy losses. Its operations finally ended on December 4, 1991, when Delta cut off its support. The airline's last scheduled flight was Pan Am Flight 436 from Bridgetown, Barbados, to Miami. The plane was a Boeing 727 named the Clipper Goodwill. Pan Am's last remaining hub at Miami International Airport was split during the following years between United Airlines, who took most of the routes, and American Airlines, who took most of the terminal space. The Pan Am brand was sold to investors and resulted in an airline that operated from 1996 to 1998, an airline that operated from 1998 to 2004, and an airline that has operated under the Pan Am brand since 2005.

In his book, Pan Am: An Aviation Legend, Barnaby Conrad contends that the collapse of Pan Am was a combination of corporate mismanagement, government indifference to protecting its prime international carrier, and flawed regulatory policy. He cites an observation made by former Pan Am Vice President for External Affairs, Stanley Gewirtz:

What could go wrong did. No one who followed Juan Trippe had the foresight to do something strongly positive .... it was the most astonishing example of Murphy's Law in extremis. The sale of Pan Am's profitable parts was inevitable to the company's destruction. There were not enough pieces to build on.

Record-Setting Flights

During the mid-1970s, there were two Pan Am flights operated around the world to set or break previous around-the-world flying records. Liberty Bell Express, a Boeing 747 SP-21 named Clipper Liberty Bell with registration number N533PA, broke the commercial plane around-the-world record set by a Flying Tiger Line Boeing 707, with the new record of 46 hours, 50 seconds. The flight left New York-JFK on May 1, 1976, and came back on May 3, 1976. The flight made only two stopovers during the journey, one in New Delhi and the other in Tokyo-Haneda, where a two-hour delay was made because of a strike among the airport workers. Nevertheless, the flight beat the Flying Tiger Line's old record by 16 hours and 24 minutes.

In order to commemorate Pan Am's 50th birthday, the airline organized yet another around-the-world flight over the North Pole and the South Pole, this time with three stopovers in London-Heathrow, Cape Town and Auckland before going back to its origin — San Francisco. The 747SP-21 used this time, Clipper New Horizons, is actually the former Liberty Bell, making the plane the only one to go around the globe over the Equator (as Liberty Bell) and the Poles (as New Horizons). The flight made it in 54 hours, 7 minutes, and 12 seconds, creating six new world records certified by the FAI. The captain who commanded this flight also commanded the Liberty Bell Express flight.

Pop Culture

Pan Am held a lofty position in the popular culture of the Cold War era. One of the most famous images of the company was The Beatles' 1964 arrival at JFK Airport aboard a Pan Am Boeing 707-331, Clipper Defiance.

From 1964 to 1968, con artist Frank Abagnale, Jr., masqueraded as a Pan Am pilot, deadheading to many destinations in the cockpit jump seat. He also used Pan Am's preferred hotels, paid the bills with bogus checks, and later cashed fake payroll checks in Pan Am's name. He documented this stage in the novel Catch Me if You Can, which became a movie in 2002. Abagnale called Pan Am the "Ritz-Carlton of airlines" and noted that the days of luxury in airline travel are over.

During the Apollo program, Pan Am sold tickets for future flights to the moon. These later became valuable collector's items. A fictional Pan Am "Space Clipper," a commercial spaceplane called the Orion III, had a prominent role in Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey, featured in the movie's poster. Plastic models of the 2001 Pan Am Space Clipper went on sale by the Aurora Company at the time of the film's release in 1968. A satire of the movie by Mad Magazine in 1968 showed Pan Am stewardesses in "Actionwear by Monsanto" outfits as they joked about the problems their passengers faced while vomiting in zero gravity. The film's sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact, also featured Pan Am in a background television commercial in the home of David Bowman's widow with the slogan, "At Pan Am, the sky is no longer the limit." (Regrettably, Pan Am did not survive into the year 2001.) In the recent sci-fi series Battlestar Galactica, one of the ships in the rag-tag fleet of survivors wandering the cosmos is a "Pan Galactic" or "Pan Gal" starliner. The ship bears Pan Am colors and the Pan Gal logo is nearly identical to Pan American's old logo.

In Japan, Pan Am was a major sponsor of sumo wrestling from 1961 to 1991 (continuing after its exit from the trans-Pacific market). Far East regional manager David Jones, who awarded the Pan American Trophy to the top wrestler at the end of each tournament, was a minor celebrity in the world of Japanese sports. The airline also lent its name and logo to a line of puzzles produced by puzzle manufacturer Tuco in the 1960s and 1970s. The puzzles depicted exotic locales that travelers might reach via Pan Am. Pan Am was also sponsor of major sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup (the only time in 1970) and the Olympic Games (the last time in 1988).

A term used in popular psychology is "Pan American (or Pan Am) Smile." Named after the greeting flight attendants (or at least actresses playing flight attendants on TV advertisements) supposedly gave to passengers, it consists of a perfunctory mouth movement without the activity of facial muscles around the eyes that characterizes a genuine smile. It was parodied periodically throughout the film Toy Story 2, where the Barbie doll was modeled after, and dressed like, a Pan Am flight attendant.